I’m currently watching “Turning Point: The Bomb and the Cold War,” a nine-part Netflix documentary that explores how two world superpowers changed the course of history. With over 100 interviews and archival footage, this remarkable documentary takes us from the probability of the Nazis developing atomic weapons in the 1930s to the present-day war in Ukraine, with its echoes of the Cold War.

1989

On the 9th of November 1989, the Berlin Wall fell, following a confused announcement from an East German official which ultimately led to the reunification of Germany. But there were many other factors at play leading up to that momentous day, not least the social democracy reforms of the last president of the USSR, Mikhail Gorbachev.

When watching scenes of jubilation and footage of young men and women climbing the wall, I was immediately transported back to 1989, a year that I will never forget.

Recently divorced and living in a scruffy one-bedroom flat in a small market town near Wales, without so much as a telephone, I was working as the sole salesman for an Australian company selling a revolutionary traction splint for EMT use. In February of that year, my employer offered me the chance to acquire the manufacturing rights to the product and go it alone, so I grabbed it with both hands and travelled the country in a beaten-up old Ford Cortina. I took my first order in a red telephone box across the road, and thus began my journey as a businessman. Later that year, I was to meet my soon-to-be second wife at a medical conference, found a house together, and built a thirty foot wooden shed at the bottom of the garden – the largest shed in town at the time, so I was told – in which I began to build traction splints for emergency services throughout the UK.

1990

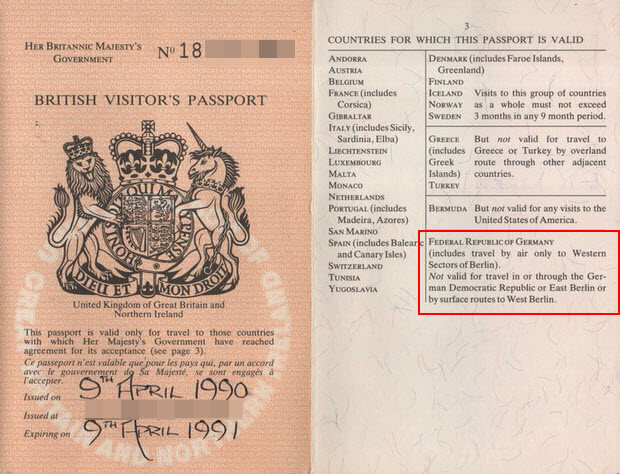

The events of 1989 eventually led to the reunification of East (GDR) and West Germany in October 1990 and the 1991 collapse of the USSR. In early 1990, I had been contacted by a medical company in Bad Salzuflen, a small town not far from Hanover, West Germany, with a view to some mutual cooperation, so we made plans to visit the firm. However, my wife didn’t have a current passport, and at that time, visitors’ passports were available, which you could get from a post office in an instant, which is what we did.

We caught the ferry from Dover to Calais, drove to Bad Salzuflen, completed our business, and then I had a brainwave.

“Hey, why don’t we drive to Berlin, now that the Wall has come down?” I suggested to my wife.

“Yeah, why not?”

So off we trundled through West Germany, but I had not taken into account that we would have to enter East Germany (German Democratic Republic as it was then) to get to Berlin. Neither had I read the small print on my wife’s visitor’s passport stating that it would not be valid in the GDR. Oops!

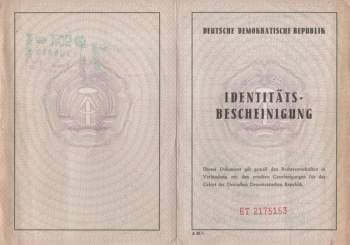

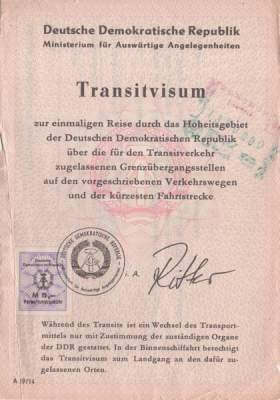

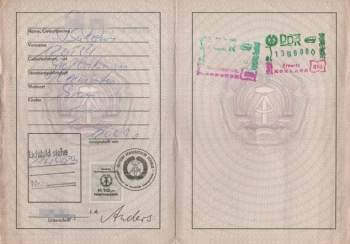

In West Germany, the autobahn was perfect with modern service stations and an abundance of everything we needed for a long journey. However, on crossing into the GDR, everything changed. The autobahn was in a terrible state, road signs looked homemade, the atmosphere was grim and foreboding, and the only service station we stopped at resembled a soup kitchen, with the only food on offer being sauerkraut and sausages served out of a massive, grimy saucepan. The downtrodden-looking lady who served us even apologised for what was on offer. We did at least manage to fill up the tank and paid in cash, which was gratefully received. If my memory serves me, it was shortly after that when we hit the police checkpoint at Drewitz, long before reaching Berlin. The car was searched, we were led into a shack, where it was discovered that my wife’s passport wasn’t valid, and we were then taken into what I can only describe as a grim-looking interrogation room. Let’s just say that some convenient tears were shed, I bargained as best I could that my wife not be detained (a real possibility it seemed at the time), I handed over a small ‘donation’ to their imaginary ‘charitable fund’, our passports were stamped, and we were on our way to Berlin! It was easter after all!

Checkpoint Charlie

We had no idea what to expect when we arrived in Berlin, but we were very excited to be there just five months after the Wall had come down. I do remember taking a photograph of Checkpoint Charlie from inside the car as we approached, but it seems to have gotten lost in all my house moves. The above photo is from Wikipedia, but it looked a lot different when we arrived. When we eventually arrived at the Brandenburg Gate, we couldn’t find anywhere to park the car and so I unwittingly parked in a restricted area, whereupon were were immediately approached by two armed East German soldiers who, although well mannered, really meant business. Threatening to arrest us for trespassing, my wife again turned on the tears, so I pointed out that Easter is a time of goodwill (I was really digging deep this time) and our ‘children’ were waiting for us back home in England, so please don’t arrest us. What struck me at the time was how deadly serious the two soldiers were, and I got the impression that they weren’t happy about the possibility of reunification and the number of tourists milling about. For those reasons, we remained extremely polite, pleaded our case, and were eventually let go after a severe warning about parking in restricted areas.

We spent the rest of the day walking around what was left of the Wall, bought souvenir chunks of it from one of the many makeshift stalls, and simply felt in awe of how East Berlin must have been before November 1989.

We didn’t stay the night in Berlin but found a hotel in a small town near Hanover, where we found a typically friendly bierkeller and enjoyed a few pints of the local brew. Now, being British, we were accustomed to paying for our drinks at the bar when ordering, but in many countries, as is the case in Germany, you settle up when leaving. But on this occasion, we inadvertently ambled out of the pub thinking we had already paid up, which we hadn’t! A minute later, the pretty barmaid came running out, caught up with us, and asked us why we hadn’t paid. You can imagine how embarrassed we were, and I wished a hole in the ground could swallow us up. Anyway, I paid her, apologised profusely (she couldn’t speak English and I couldn’t speak German), and she accepted our pleas. But I couldn’t leave it at that, so I found a flower shop, bought a single red rose, dashed back to the bierkeller, and presented it to her. She melted before the rose and kissed me on the cheek with a smile.

After that, we made a dash for Calais, believing that perhaps our luck was running out…

That’s my memory of 1989 and its effects. What’s yours?

—

I was able to SHARE this story on Fascist Book just now. Your ban must be over.

That was sorted out quite some time ago, but thanks for sharing the article, Charles.

It was for myself, I lost my first wife in July of 1989!!!